Thousands of people made the shields and shipped them to the camp at Standing Rock — and both the mainstream and visual arts media took notice.

The shields were, of course, symbolic, but creating them allowed people to show their empathy for an environmental movement, to do something.

“The statement kept coming up: ‘I’m one person. What can I do?’,” Luger said in an interview last week.

“Well, that video was about how one person could make six shields. And those six shields could stand in front of 20 people in prayer on the front lines. And those 20 people stood in front of the whole camp, which was several thousand people. And those people were in front of eight million people downstream.”

The shields, Luger points out, are just part of a larger body of work that aims to connect people to the land around them and to consider the consequences of how we treat it. Two examples of his efforts are on display in Denver galleries currently.

At the Center for Visual Arts, Luger and fellow members of his art collective, the Winter Count, are part of the group show “WaterLine: A Creative Exchange,” curated by Cecily Cullen, which features an international lineup of artists focusing on threats to the world’s water supply. Luger’s showiest piece is called piece is called “This Is Not a Snake” and is constructed from oil and chemical barrels, old tires and other refuse, which come together in the form a snake, about 30-feet long, with a ceramic head at either end. It is ominous and very bit the “monster” Luger describes it as.

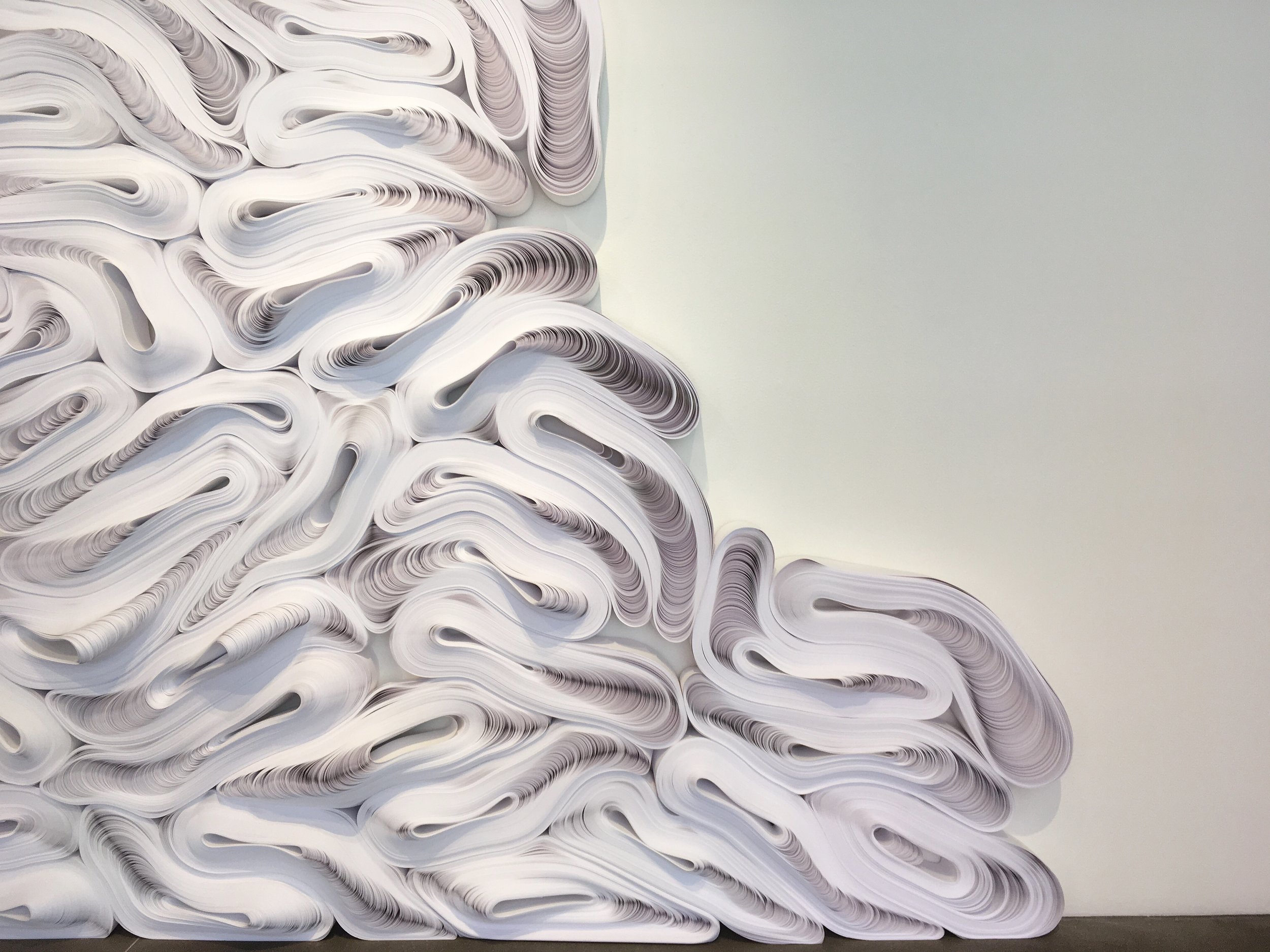

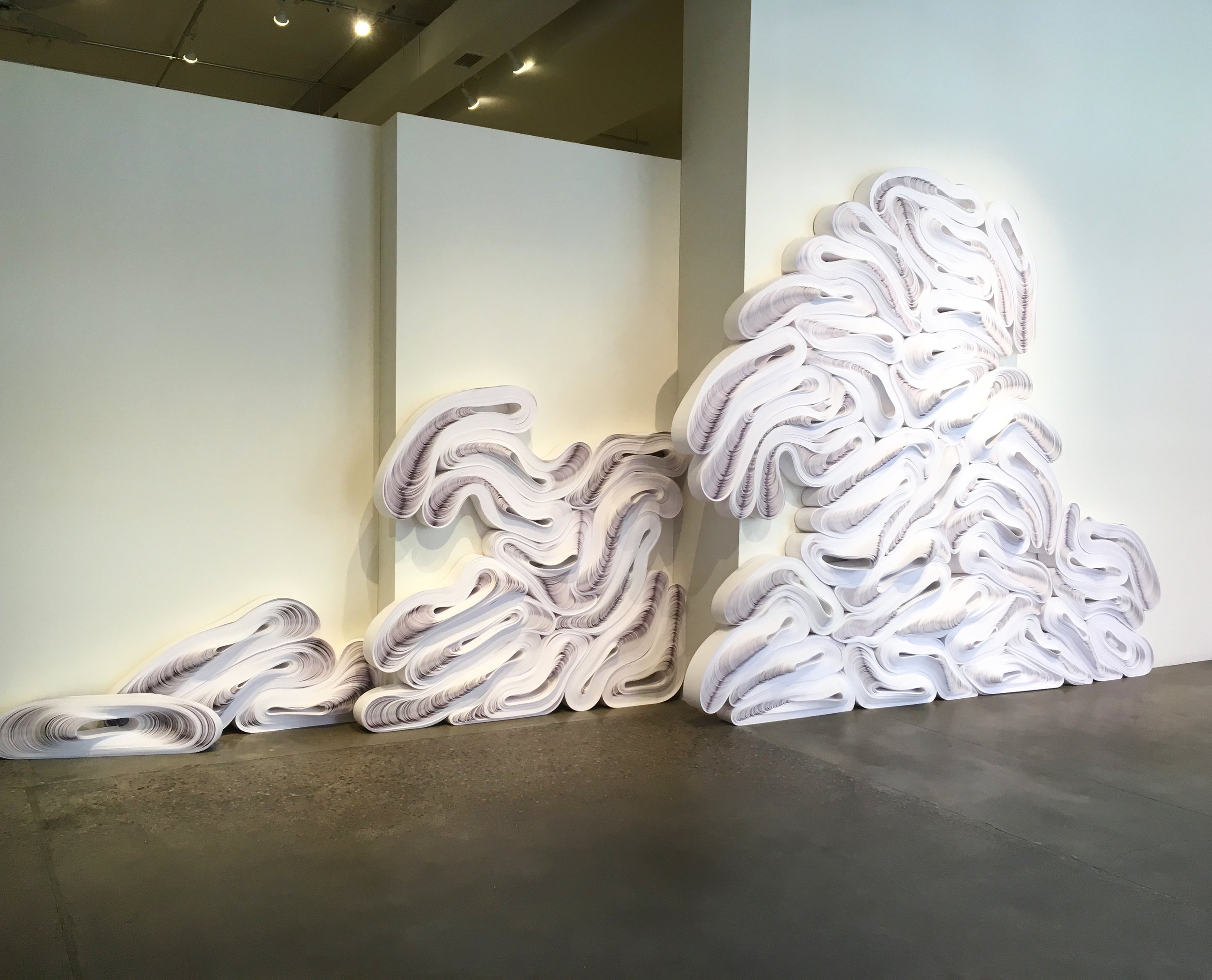

At RedLine, he is producing two related works. A performativepiece, which features a small troupe of local dancers, and an immersive installation that has his now-familiar shields set before landscape videos captured via drones in the air. The exhibits are co-curated by Libby Barbee and Kirsten Walsh.

The gallery works are different but “both are disembodied parts of the same body,” he says, and they both focus attention on the ground beneath our feet.

“By opening up conversation around landscape and giving landscape a voice,” he said. “You are then talking about everything that’s connected to it — the people, the plant life, the water itself.”

That conversation about earth and water, Luger says, is crucial to Winter Count’s mission of employing art as activism. He calls it a way of “weaponizing my privilege.”

“Working in the art industry gives us all these tools. You have access to media, access to institutions and, through those, access to communities,” he said. “We started asking ourselves what’s the point of having this level of privilege if you’re not doing something to help us all.”

Luger’s background is a combination of American Indian and European: “Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, Austrian, and Norwegian,” as his official bio puts it together. He was born and raised on the Standing Rock Reservation, and much of his focus is on issues that are important to native people.

During the protests, he drove his own vehicles back and forth between Glorieta, New Mexico, where he lives and Standing Rock eight times, delivering supplies — water, blankets, wood stoves, jackets, “whatever anybody could offer at the time” — to the protest camps.

His art, he said, is another way of supporting indigenous causes. Though it comes at things in a less direct form.